Why C++ is Far From Dead - Despite Rust

The characteristics of embedded systems typically include limited resources, hard real-time requirements, and product lifecycles spanning decades. Traditionally, C dominates this domain because the language offers full control over hardware and minimal overhead. However, the complexity and requirements of modern embedded applications are increasing: networking, over-the-air updates, complex state machines, and security requirements take their toll.

This is where modern C++ comes into play. With standards from C++11 to C++23, the language has fundamentally evolved and now offers abstractions that operate without runtime overhead (zero-cost abstractions). Moreover, features like constexpr, RAII, templates, and strong typing enable writing more robust and maintainable code without sacrificing the control or efficiency required in embedded systems development.

Why Not Rust?

Rust is gaining attention in the embedded world. The language promises memory safety without a garbage collector, enforces thread safety at compile time, and does so with similar performance to C/C++. These are attractive properties for safety-critical systems. Nevertheless, C++ remains the more pragmatic choice for many projects: toolchain support is mature, existing C code can be modernized incrementally, and the developer pool is significantly larger.

In this article, we show how modern C++ (partially) bridges the gap between C's control and the safety guarantees of newer languages like Rust.

Containers

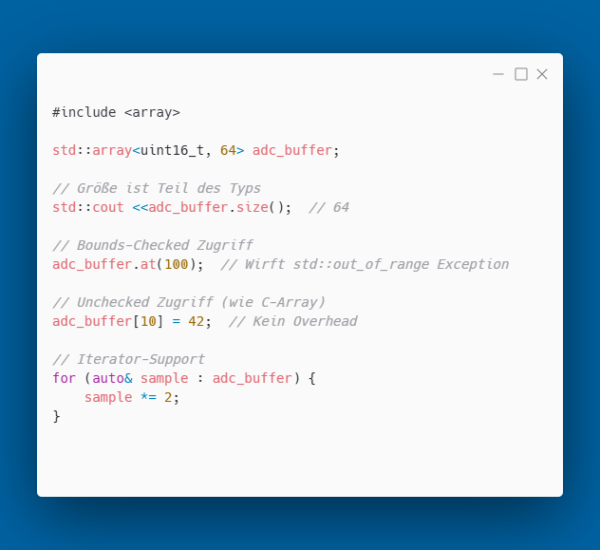

Arrays are ubiquitous in embedded systems: buffers, lookup tables, register mappings. C arrays are unsafe because they have no boundary checks and size information is quickly lost. C++11 introduces std::array and C++20 adds std::span for safe array views.

std::array - Type-Safe Fixed-Size Array

std::array is a zero-overhead wrapper around C arrays. Same performance, better safety:

Defensive Programming with at(): In embedded systems, exceptions are often disabled (-fno-exceptions). In case of an out-of-bounds access with at(), the behavior is implementation-dependent. Typically, the standard library calls std::terminate(), which by default terminates the program. This sounds dramatic, but is better than silent data corruption through buffer overflows. With a manual check, you handle cases where out-of-bounds access is expected, and with at() you catch bugs that slip through. With a custom terminate handler, you can define the behavior - such as error logging, safe state, or controlled reset.

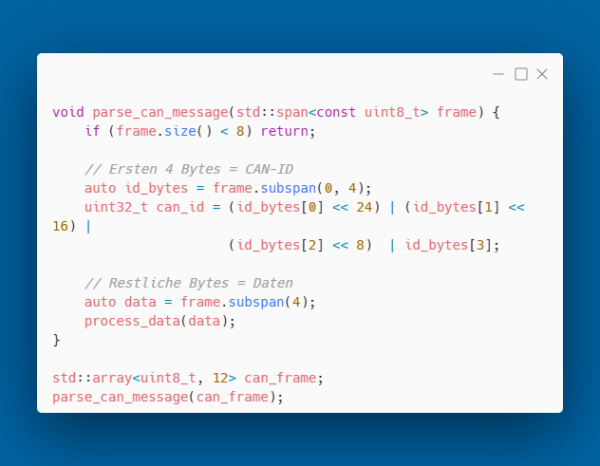

std::span - Type-Safe Array Views

std::span from C++20 is a "view" on a contiguous array. It solves the problem of array passing. Memory location and size are combined in a type that allows safe access through iterators, for example:

Sub-Spans - Safe Slicing

std::span allows safe splitting of arrays:

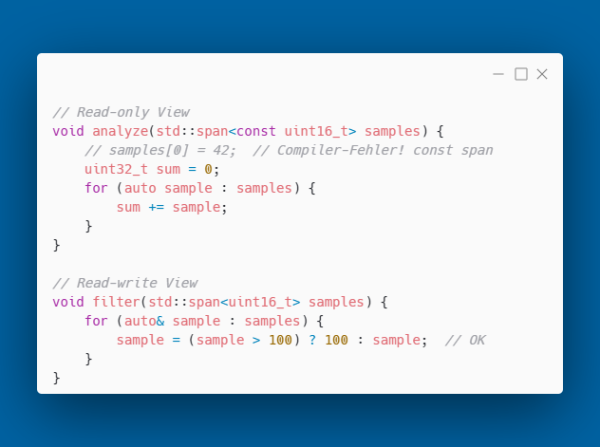

Const-Correctness with span

Enum Class

Traditional C enums have several weaknesses: they pollute the global namespace, convert implicitly to int, and offer no type safety. C++11 introduces strongly typed enumerations with enum class.

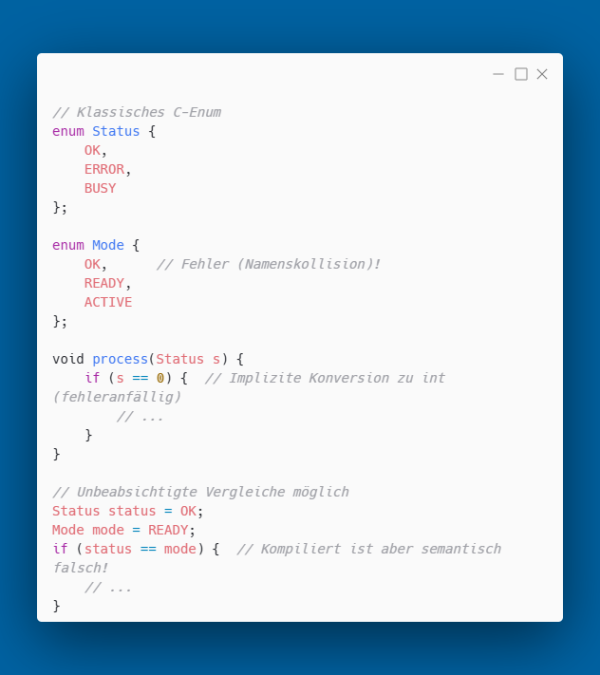

The Problem with Classic Enums

Strong Typing

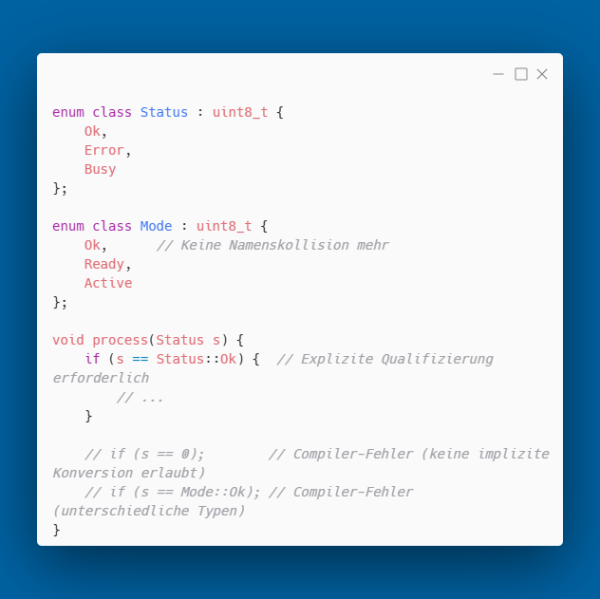

enum class solves these problems through its own namespaces and prevents implicit conversions:

The compiler enforces correct usage. Typos and mix-ups are caught at compile time.

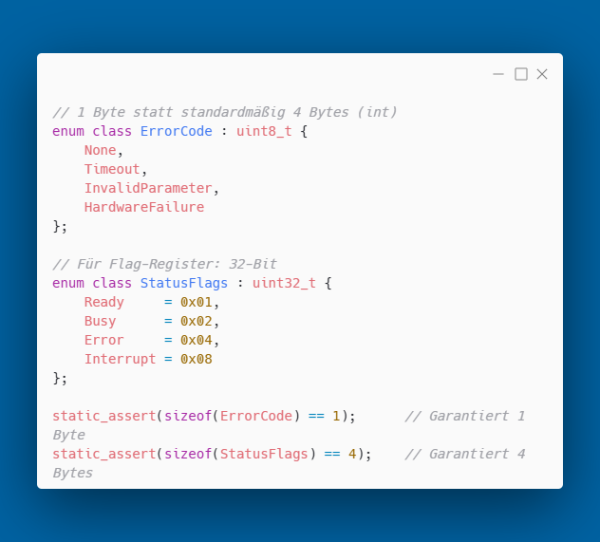

Control Over Storage Size

In embedded systems, every byte counts. Enum classes allow explicit specification of the underlying type:

Explicit Conversion When Necessary

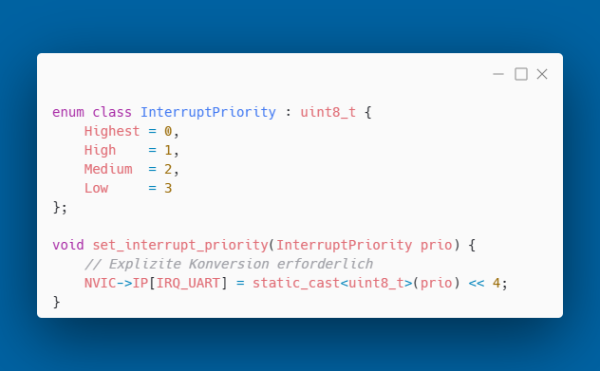

Sometimes access to the underlying value is necessary, such as when writing directly to hardware registers:

The explicit conversion makes it clear that a type boundary is being deliberately crossed here. C++23 introduces std::to_underlying(), a function that automatically detects the underlying type. Instead of static_cast(prio), you write std::to_underlying(prio), achieving more type-safe and readable code.

Compile-Time Calculations

Modern C++ offers type-safe compile-time calculations directly in the language. The compiler calculates the result and stores it directly in ROM without runtime overhead.

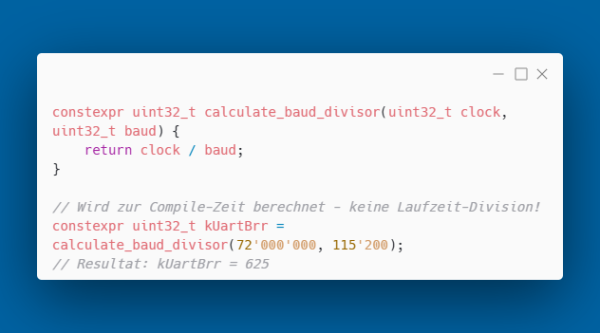

Constexpr - Compile-Time Calculations

With constexpr (since C++11), functions and variables can be marked to be evaluated at compile time.

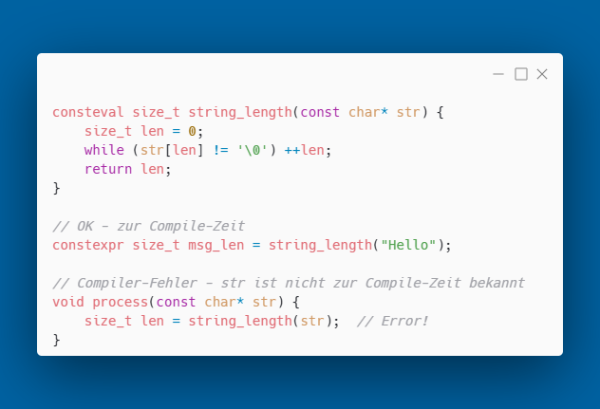

Consteval - Guaranteed Compile-Time Evaluation

C++20 introduces consteval, a stricter version of constexpr. Functions with consteval must be evaluated at compile time; a runtime call is a compiler error:

This guarantees that resource-intensive calculations are never accidentally executed at runtime.

RAII

RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization) is an idiom in C++ for automatic resource management.

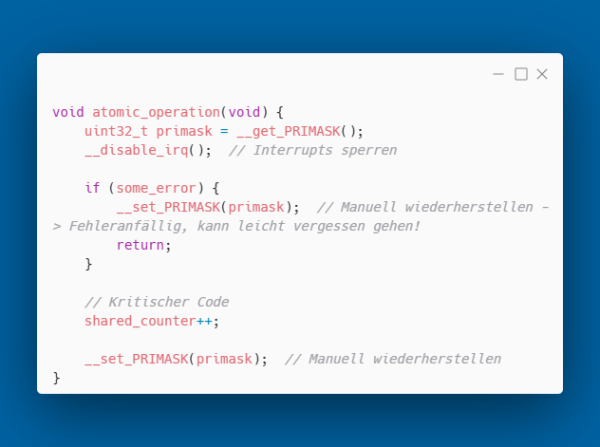

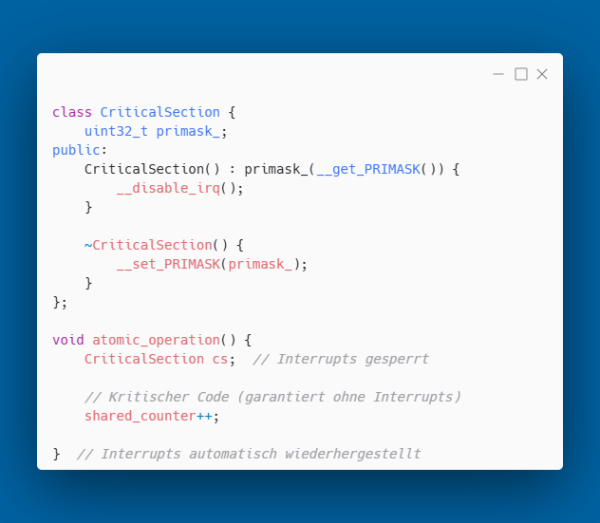

The Basic Principle

The idea is simple: resources (memory, hardware peripherals, interrupts, mutexes) are acquired in an object's constructor and automatically released again in the destructor. The compiler guarantees that destructors are called, even with early returns. In C, a CriticalSection looks like this:

Each error case requires manual cleanup. In more complex functions, this leads to duplicated cleanup code and potential resource leaks. With RAII, the resource is encapsulated in a class:

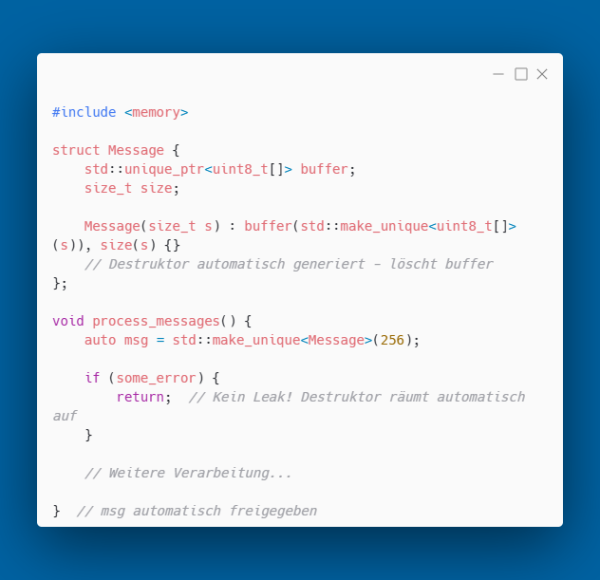

Smart Pointers

Smart pointers from C++11 bring automatic memory management to C++. In embedded systems, their use is controversial due to dynamic memory allocation. However, there are legitimate use cases and smart pointers make them safer.

std::unique_ptr - Exclusive Ownership

std::unique_ptr guarantees exclusive ownership of an object. There is exactly one owner and when leaving the scope, memory is automatically released. This abstraction is completely without runtime costs and the generated code corresponds to a manual delete.

Transfer Ownership with move

unique_ptr cannot be copied, but can be moved:

The compiler enforces clear ownership relationships.

std::shared_ptr - Shared Ownership

shared_ptr allows multiple owners through reference counting. The resource is released when the last owner is destroyed.

Unlike unique_ptr, shared_ptr has overhead and additional memory is allocated for the reference counter and atomic operations for thread safety. It is recommended to use this pointer type only when really necessary.

Conclusion

The features shown are just a snippet; modern C++ offers much more: std::optional and std::expected for explicit error handling, std::variant for type-safe unions, concepts for type-safe template constraints, and much more.

However, C++'s legacy issues remain, such as undefined behavior, manual memory management, or missing borrow checkers. The responsibility lies with the developer to use new and safe concepts. Those who continue to use raw pointers instead of smart pointers, C arrays instead of std::array, manual loops instead of range algorithms, forfeit the advantages. The language offers safe alternatives but doesn't enforce them. Coding standards, code reviews, and continuous education are therefore essential components of successful embedded software development to actually deploy modern C++ and leverage its benefits.

Rust, on the other hand, was developed from the beginning with the goal of being safe. Many problems that developers must handle themselves in C++ are already safely eliminated by the language in Rust. From a security perspective, Rust is a better choice compared to C++.

However, Rust is still young compared to C++, which means there are fewer experienced developers and a smaller ecosystem of libraries. Therefore, C++ remains a relevant language even today.

Nicola Jaggi

BSc BFH in Electrical Engineering and Communications Technology

Embedded Software Engineer

About the author

Nicola Jaggi has been an embedded software engineer at CSA Engineering AG for 11 years, focusing on C++ firmware on STM32.

CSA Engineering AG supports companies in the design and development of modern embedded software.